To put it lightly, vacations weren’t the most pleasant form of R&R during the time of WWII. Stories of death and devastation unfolding on the other side of the ocean were inescapable and plentiful. Even if you could find a place to get away from all the dread, you’d run into transport issues.

To put it lightly, vacations weren’t the most pleasant form of R&R during the time of WWII. Stories of death and devastation unfolding on the other side of the ocean were inescapable and plentiful. Even if you could find a place to get away from all the dread, you’d run into transport issues.

Automobile owners were severely handicapped as rationing of gasoline began in order to offset the lack of supply of raw rubber. As a result, public preference shifted and began to put a strain on other forms of transport like car-pooling, public transport, and railway.

Unfortunately, the railway system was already burdened. Largely being used by the government to mobilize troops and war equipment, the railway companies found their resources stretched too thin between serving the military and the public. As a matter of priority, it was the public that eventually suffered.

Stations were overcrowded with people. Young boys would be lined up to enlist for battle while families and loved ones could be seen tugged on to train windows to say their goodbyes. The situation inside the trains wasn’t any more comforting. Due to lack of space, many public travelers had to sit on their luggage and sleep sitting up. The food was scarce, and most other facilities were stripped off to make room for everyone.

Naturally, the outpour of discontent passengers started filling up mailboxes at the New York, New Haven, and Hartford Railroad offices (commonly referred as New Haven Railroad). The biggest complaints being delays, crowding and priority allocation of sleeping berths to military personnel.

What’s peculiar about the public’s resentment on railway services was its magnitude and timing in the backdrop of a war which the U.S was forcefully dragged into. At a time where every radio station, newspaper, and newsreel continuously discussed the indispensable service being carried out by U.S forces across continents, people were bitter about their lack of comfort.

To reel in the public sentiment, the New Haven Railroad looked towards its advertising agency to come up with a solution. The ultimate creative responsibility came down to a copywriter within the agency named Nelson C. Metcalf, Jr.

His first ad tried to tackle the issue by highlighting the strain caused by the railway system by the amount of war freight they were forced to move. The ad ran by the name of “Right of Way for Fighting Might”. It didn’t amount to much and the complaints kept coming. His second attempt, titled “Thunder along the Lines”, although different from the first, stayed within the lines of justifying the conundrum the railway system was trapped in. This too didn’t tip the public’s needle over New Haven’s favor.

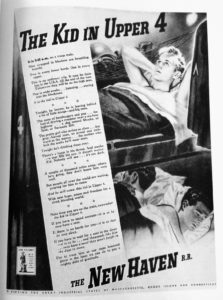

It wasn’t until his third attempt that struck the right chords within people’s hearts. “The Kid in the Upper 4”, although printed on page 18 of the New York Herald Tribune, garnered instant public support. Its impact resonated so deeply that it turned up in songs, movie shorts, bulletin boards and magazines.

It’s called the single most famous advertisement of the war and included in the 100 best advertisements of all time.

It is 3:42 a.m. on a troop train.

Men wrapped in blankets are breathing heavily.

Two in every lower berth. One in every upper.

This is no ordinary trip. It may be their last in the U.S.A. till the end of the war. Tomorrow they will be on the high seas.

One is wide awake … listening … staring into the blackness.

It is the kid in Upper 4.

Tonight, he knows, he is leaving behind a lot of little things – and big ones.

The taste of hamburgers and pop … the feel of driving a roadster over a six-lane highway … a dog named Shucks, or Spot, or Barnacle Bill.

The pretty girl who writes so often … that gray-haired man, so proud and awkward at the station … the mother who knit the socks he’ll wear soon.

Tonight he’s thinking them over.

There’s a lump in his throat. And maybe – a tear fills his eye.

It doesn’t matter, Kid. Nobody will see … it’s too dark.

A couple of thousand miles away, where he’s going, they don’t know him very well.

But people all over the world are waiting, praying for him to come.

And he will come, this kid in Upper 4.

With new hope, peace and freedom for a tired, bleeding world.

Next time you are on the train, remember the kid in Upper 4.

If you have to stand en route – it is so he may have a seat.

If there is no berth for you – it is so that he may sleep.

If you have to wait for a seat in the diner – it is so he … and thousands like him … may have a meal they won’t forget in the days to come.

For to treat him as our most honored guest is the least we can do to pay a mighty debt of gratitude.

By January 1943, competing railroads had full-color posters of this ad on their terminals, while the New Haven Railroad company, its advertising agency, and copywriter Nelson C. Metcalf, Jr. received roughly 10,000 letters in praise of the ad campaign and for reinvigorating their respect for the military and its servicemen when it counted most.